Government functions cost money

Government carries out functions to better serve us, and these cost money. Some of these are fixed costs, some of these increase with the size of the population, some vary with periodic problems (e.g. wars, depressions, etc.). But let’s say that all the functions of our hypothetical government cost $1,000,000,000/year. The government is empowered to raise revenue to meet this cost. How can we pay for these things?There are generally two options here: Fees for service, and distribution. A fee for service is when people using a particular service pay the cost of the service, like the U.S. Postal Service or Amtrak. Most government services aren’t easily apportioned by use, defense being a good example. Sometimes a mix of fees and distribution.

For the purposes of this example, we’ll assume that all of the costs are best distributed.

Equal distribution

On first glance, it seems that the fairest thing to do is to split the cost evenly among the entire population of the country. Let’s say that this hypothetical country has 100,000 people in it. That would be $10,000 per person per year. However, not everyone can afford $10,000 a year, if they even had that much to give in the first place. So at best, the government wouldn’t be able to raise the money it needed to carry out its functions, and at worst, it would seriously harm the ability of the poorest people to get by. By necessity, we would need to scale the taxes by an individual’s income.Flat tax

A simple way to correct for this is to look at the the total income citizens receive and figure out what percentage of that you need to collect to make up the cost of government. Let’s say the total income of this hypothetical country is $10,000,000,000. In order to collect the $1,000,000,000, assessing a tax of 10% of everyone’s income would suffice. To an approximation, this seems like a fair way to do it, and this is the approach supported by some conservatives.Progressive tax

One of the problems with a flat tax approach, however, is that 10% of someone’s $20,000 income hurts them a lot more than 10% of someone’s $2,000,000 income. Consider also that people with more assets and higher income are more heavily using government services in general than those with fewer assets and lower income. Add the stated American ideal of economic mobility into the mix, and people at the lower end need more of their money available to give them an opportunity to work their way up (or back up) in the world. Given these considerations, it makes sense to tax lower incomes at a lower rate than higher incomes.A more practical concern is how to make sure that the taxes are continuous as income increases. This is where we get marginal tax rates from: the first part of someone’s income is taxed at one rate, the next higher part at another rate, and so on.

Just deciding to have a progressive tax is one thing, but deciding how to tilt the balance is quite another. If you have a fixed target income for the government, you need to account for the distribution of incomes in the country, and for every bit the lower rates are decreased, the upper rates have to be increased.

Special tax rates

Once you have this system set up based purely on income level, it might still be beneficial to reduce someone’s taxes based on specialized circumstances. For instance, maybe you exempt a certain base portion of income from taxes (essentially setting a 0% income bracket). Or maybe if someone suffers a major loss, you can allow them to offset some of their income to reduce their taxes. Or perhaps there is an economically-burdensome activity that should be incentivized, like recycling electronics or buying a home. Or maybe people with certain disabilities or are supporting families need a bigger break than a single person. There are two ways the government can do this: reducing the taxable income with a deduction or exemption, or directly reducing taxes owed with a credit. The effective difference between a deduction and exemption is that an exemption has to do with the person and those supported by them, while deductions come from what someone spends their money on.In addition to direct adjustments, you could also treat certain kinds of income differently and apply a special rate to them. An example of this is for capital gains—money you make from investments.

A lot of problems creep in at this point. Too many makes the process of calculating one’s taxes much too confusing and prone to error. Additionally, they can introduce items that end up compromising the progressive tax scheme by allowing people and/or businesses that have make a lot of money to engage in behaviors that sharply reduce or, at times, eliminate their tax burden.

Brief history of the progressive income taxes in the United States

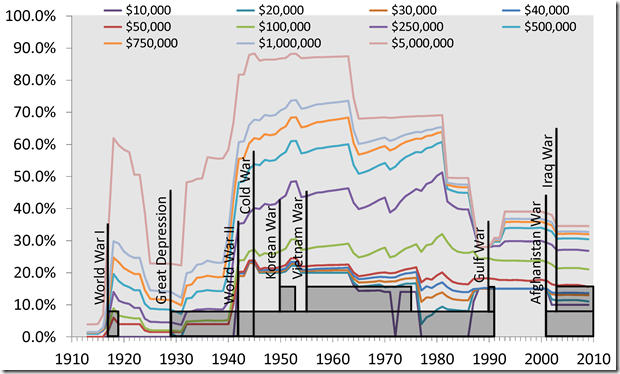

Before I end this post, I wanted to show features of the progressive income tax in the United States from its inception. The graph was constructed from information taken from the Tax Foundation and shows the effective tax rate for earned income in inflation-adjusted 2010 dollars. I have also overlain some of the major events of American history over this period as a reference.When federal income taxes were implemented in 1913, rates increased in seven steps from 1% under $20,000 to 7% over $500,000. In 1916, more brackets were added, with 12% over $500,000 and 15% over $2,000,000. In 1917, the low end of the scale was broken up more finely, with 2% under $2,000, 9% under $20,000, and 67% over $2,000,000. In the 1980s, the tax brackets were reduced to the handful that we are familiar with today and they began being adjusted for inflation every year, which is why the effective rates on the graph look more stable.

Notable observations:

- We raised taxes to pay for World War I. We raised taxes during the Great Depression, and again to pay for World War II and anti-Communism activities. We only decreased tax rates somewhat towards the end of the Cold War and then again in the after 2001.

- Effective tax rates for the highest incomes today are far lower than they have been for most of our history. And as highlighted by recent news about extremely profitable corporations owing no income taxes (and even receiving refunds), and people with very high incomes owing much less in taxes than the earned income tax rate would suggest (e.g. Mitt Romney’s 14.5% over two years).

Is there any historical data available on the actual, paid income tax rate for different income groups? I mean, the data you reference - as far as I understand - is the rate for taxable income. But what if we take deductions into consideration, and calculate the rate based on how much money one pays in taxes in total versus how much money one earns. So that if someone made $10,000,000 in 1950, but had deductions worth $5,000,000, and so only paid around 70% of the remaining $5,000,000, we would say the actual, paid tax rate would be 35% (5,000,000*0.70/10,000,000).

ReplyDeleteThat is a fair point, primarily because that would have taken more time than I had to look into. I did use the standard deduction and a standard exemption, but obviously anyone who would itemize would have a larger deduction than that (and those who had higher incomes, like today, more likely did that).

DeleteHowever, I think a more salient point is that with a larger income tax on higher incomes and sensibly-directed deductions even if the effective tax on gross income isn't at the nominal percentage, it would still be spent by the individual rather than retained. More than anything else, a healthy economic system depends on fluid movement of money and resources evenly throughout the economic spectrum, and that's not happening right now.

I researched the subject further and found out that someone had indeed done the numbers. I'm linking to the graph I've made from the data. I got the data from the Congressional Budget Office here: http://www.cbo.gov/publication/41654

DeleteI've overlapped that data with the marginal tax rates using data from the Tax Policy Center: http://www.taxpolicycenter.org/taxfacts/displayafact.cfm?Docid=213 - so we can see how that affects the actual, paid tax rate. Unfortunately, CBO only has data from 1979-2005. But it's better than nothing. Enjoy :)

http://i.imgur.com/8sdol.png

Very interesting... thank you for doing that. For comparison back to my graph, the top 1% in 2005 was at ~$1,200,000 in 2005 dollars.

Delete