Tracking and Communicating About Variants

Say the words “Alpha”, “Delta”, or “Omicron” today and

virtually the whole world knows what you are talking about: a variant of the

virus that causes COVID-19.

This universal awareness is the result of a phenomenally successful choice by the World Health Organization (WHO) to provide Greek letter names to the major variants of the virus that have evolved over the course of the pandemic (WHO variants page). Providing these names avoided a choice between the inaccessible and confusing Pango nomenclature (e.g. “B.1.1.7”, "B.1.351", "B.1.617.2"), and inaccurate and stigmatizing place names (“e.g. “UK variant,” “South African variant,” “Indian variant,”).

Between mid-2020 and the end of 2021, 10 major variants had been named.

No new major variants have been named since Omicron was named

in November 2021.

However, this lack of new names is not because no new major variants have emerged. Rather, they’re all lumped into “Omicron” now. And this mistake can be traced back to the initial naming of Omicron.

Enter Omicron: Two Variants with One Name

Late in 2021, the B.1.1.529 lineages emerged which would be

designated “Omicron”. These lineages had a much larger constellation of amino

acid changes than any previous named variant, especially in the pathology-determining

spike protein. However, virologists never observed B.1.1.529 itself. Instead,

two highly diverged lineages, BA.1 and BA.2 (in Pango,

“BA” is short for “B.1.1.529”). For context, the divergence between BA.1 and

BA.2 is the same magnitude as the difference between Alpha and Delta.

|

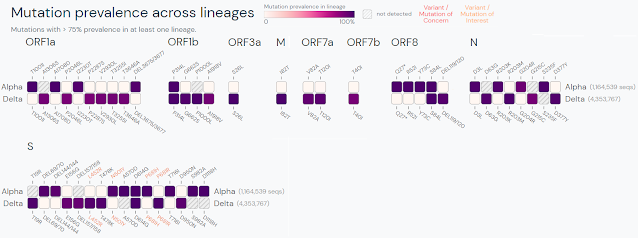

| Comparison between Omicron BA.1 and BA.2 via Outbreak.info. Purple indicates a difference from the ancestral strain. |

|

| Comparison between Alpha and Delta variants via Outbreak.info. Purple indicates a difference from the ancestral strain. |

In a February 22, 2022 statement, the WHO announced that studies had shown BA.2 has a growth advantage over BA.1 due to inherently higher transmissibility; that there was evidence of some reinfection capability; and that disease severity may be higher in immune-naïve individuals. The WHO also acknowledged that it was increasing in relative prevalence.

BA.2 is also uniquely resistant to the therapeutic

monoclonal antibody Sotrovimab, which led the FDA to restrict usage in regions with elevated levels

of BA.2 spread. BA.1, in contrast, is partially resistant to the dual

monoclonal therapeutic Evusheld (NIH Treatment Guidelines). Two recent

independent analyses (Science

Immunology, medRxiv

(preprint)) also demonstrated that BA.1 and BA.2 are as distant from each

other in “antigenic space” (that is, different to the immune system), as the

most divergent pre-Omicron named variants were. These findings are the reason

why BA.5 (a close relative of BA.2) was chosen for the new booster vaccine dose in the United

States, since BA.5 and other BA.2 relatives are currently dominant.

|

| Comparison between Omicron sublineages BA.1, BA.2, BA.2.12.2, BA.4, BA.5 via Outbreak.info. Purple indicates a difference from the ancestral strain. |

In sum, BA.2 (and its relatives) have demonstrated increased transmissibility, increased naïve severity, increased immune evasion, and therapeutic differences vs. BA.1, meeting several WHO criteria for naming a new variant. However, the WHO decided to maintain the Omicron label and has set a high threshold of proof to assign a new name.

Why is the WHO Reluctant to Name Variants?

We have no solid explanation for why the WHO has effectively jettisoned its successful naming system. Several WHO officials and scientists charged with advising on the COVID-19 response have variously described reasons that amount to a kind of institutional inertia and bureaucratic blindness, among them Dr. Marion Koopmans, Dr. Tulio de Oliviera, and Dr. Maria Van Kerkhove. The consensus of their views seems to be that the WHO's job ends once a variant of the ancestral strain is declared "of concern", there's a reluctance to disrupt the widespread view of Omicron as "mild", and they don't understand the utility of providing the public with a name.

Regardless of how we got here, the

public needs clear guidance from scientists and policymakers about what is

happening in the world they live in. Keeping the same name communicates to the

public that the current variants are interchangable. But because there are

clear differences in transmissibility, immune evasion, and/or therapeutic

effectiveness between them, regulatory agencies, policymakers, and news media

have had to revert to using the Pango nomenclature to communicate to the public

about the state of the pandemic (White

House, Los

Angeles Times).

Omicron Should Be Split

The WHO should treat sublineages of named variants the same as sublineages of the original variant. The threshold for sublineage naming should also come well before the variant drives a major global wave of infection, when alerting and informing the public and policymakers is most critical.

At an absolute minimum, Omicron should be split into Omicron (BA.1) and Pi (BA.2). The BA.2-related sublineages should likely be further split into Rho (BA.2.12.1), Sigma (BA.4), and Tau (BA.5). Emergent sublineages with large numbers of mutations, such as BA.2.75 (nicknamed on Twitter as “Centaurus” (BA.2.75 comparison)) should also likely receive a name sooner or later.

Conclusion

The public needs clear guidance from scientists about what is happening in the world they live in. Telling the public that BA.1, BA.2, BA.4, BA.5, etc. are all “just Omicron” when there are clear differences between them in transmissibility and/or immune evasion is doing them a disservice. The public and policymakers need a way to talk about these sublineages. We need the scientists at the WHO to step up and provide leadership by naming the variants we need to communicate to the public about.

No comments:

Post a Comment